How to paint a black & white portrait in Oils a Step by Step approach

In this series of 5 posts, I am going to look at the process of how to tackle painting a black & white portrait using oil paints.

So when you come back to your painting the next day, it’s a good time to reassess the drawing and have another look at the tones…

What we’re going to do to start with, is to strengthen the background and shadow tones, still using just the Raw umber.

Because Raw umber is a quick drying pigment it still sits in the principle of fat-over-lean but to make sure, we’re going to add some Linseed oil to our Odourless Mineral Spirits (OMS) to create our paint medium.

Mediums in Oil Paint

A medium is something added to the paint whilst mixing colours on the palette. Different artists vary greatly in their preferred choice of mediums. Mediums can help with blending, glazing, brush techniques and the handling qualities of the oil paint.

Mixing Raw umber for this layer

For this Raw umber part of the demonstration we will be using a very simple mix of OMS and refined Linseed oil, 1 part linseed oil : 4 parts mineral spirits

To add the oil to the OMS, I use a pipette. They make it easy to judge exact proportions and help keep a clean working environment.

The one thing to remember with a medium is less is more, you only need such a small amount of it otherwise you find yourself chasing the paint around the canvas instead of being able to scrub it in.

Refined Linseed Oil: made from the seeds of the flax plant. It adds gloss and transparency to paints and is available in several forms. It dries very thoroughly, making it ideal for underpainting and initial layers in a painting. Refined linseed oil is a popular, all-purpose, pale to light yellow oil which dries within three to five days.

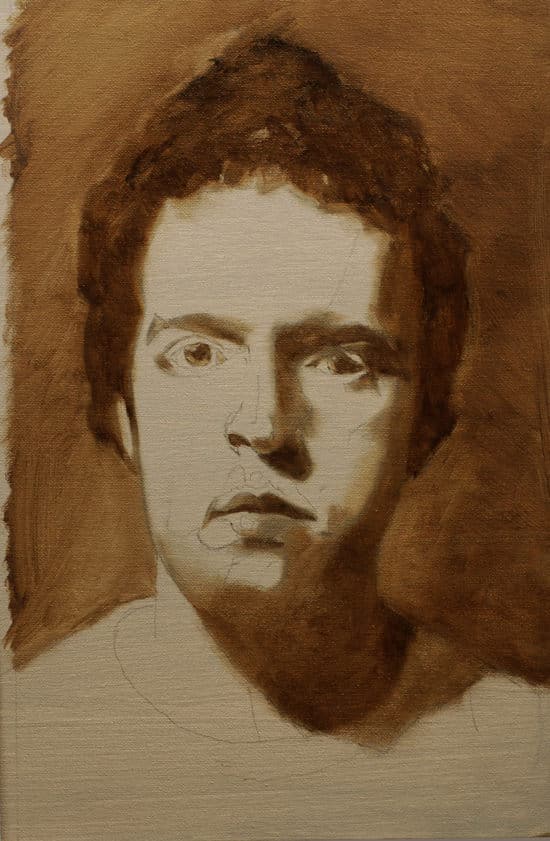

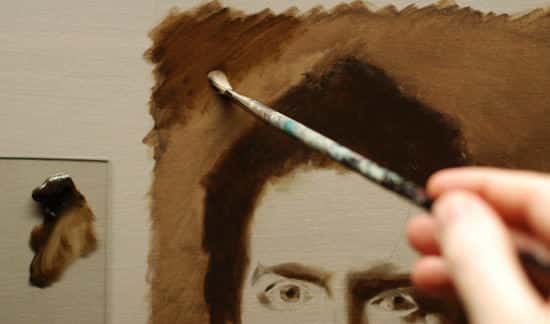

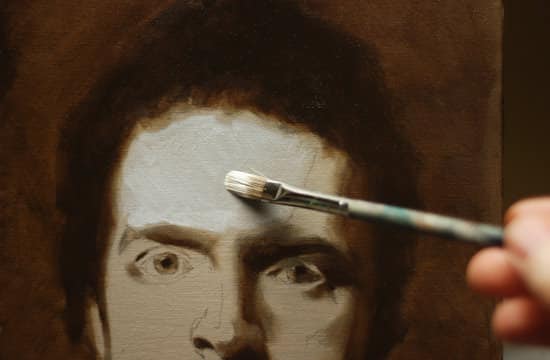

Step 9 – Strengthening the Shadows

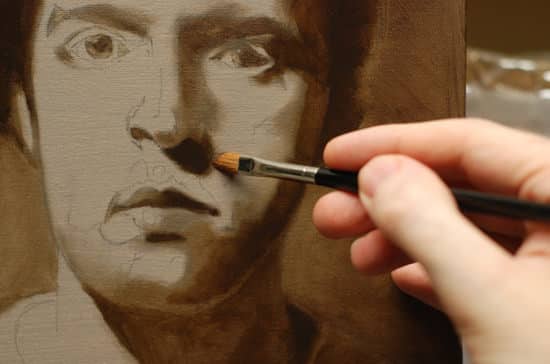

I now dip my brush in the medium, then take the excess off on kitchen roll until the brush is damp but not wet. I then paint on a slightly thicker layer of paint over the hair to reinforce the tones – the darkest dark and get closer to the reference photo.

I’ve also reinforced the shadow line on the side of the face and under the chin, this was using the size 4 Ivory Filbert, notice how I haven’t blended the edge yet due to the scale of the portrait being quite small.

I will swap to a Sable to have more control and dry brush and fuse the edge.

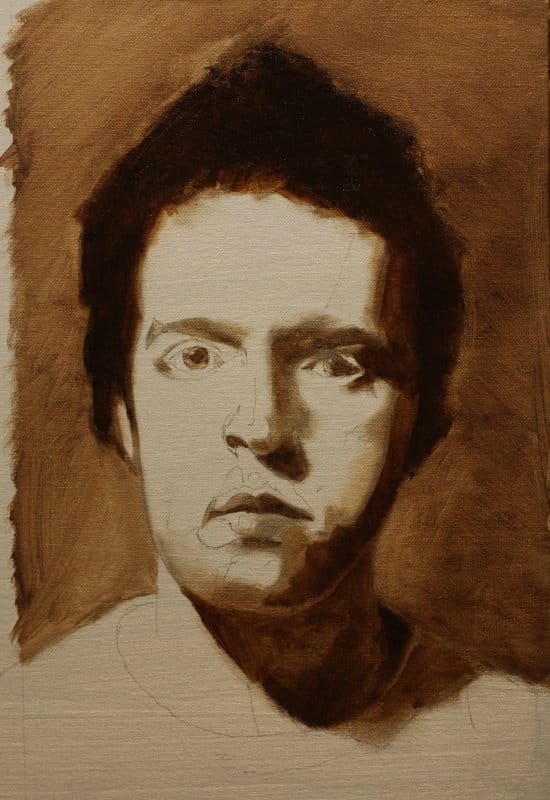

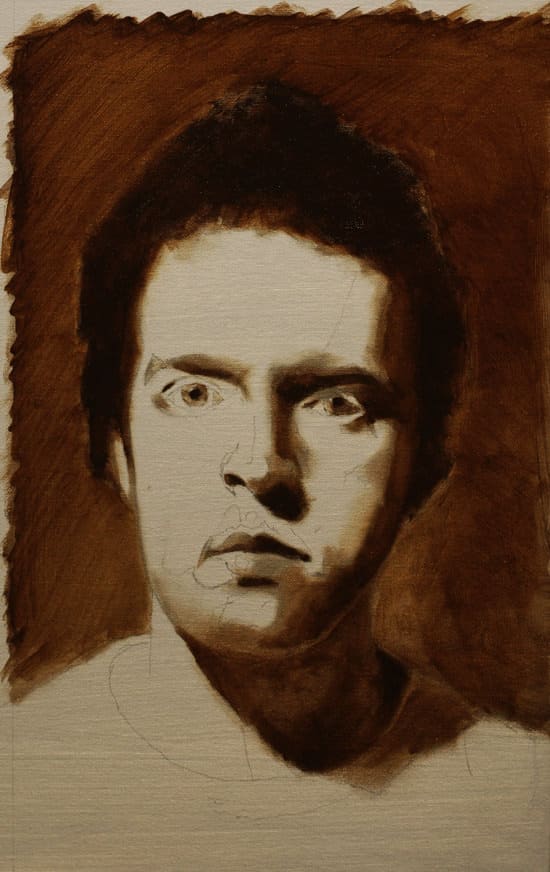

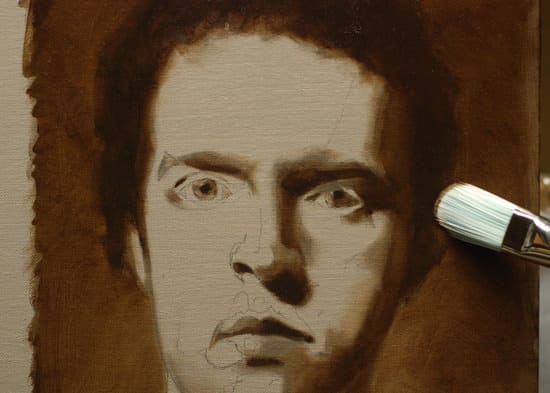

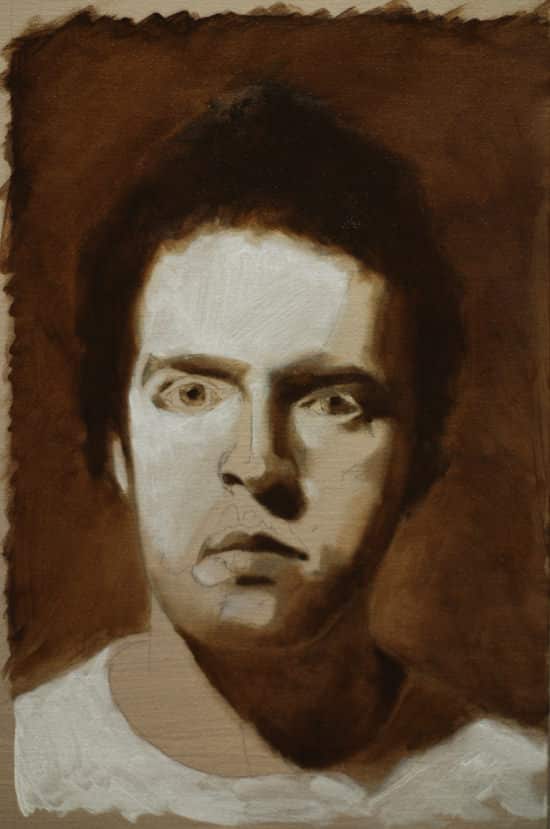

Step 10 – Adding more darks on the features

So now squint your eyes at your painting and the reference photo and still think of simple shapes, don’t get hung up on trying to paint the details – just concentrate on the shadow shapes, and look for the areas of the darkest dark around the portrait.

I’ve now added the Raw umber around the eyes, top lip and the neck, using a smaller, Round brush. These are the areas that need to go darker, it’s at this point you can check your drawing again.

It’s natural to feel that you might be going in too dark at this stage but feel confident that we haven’t used black paint yet, so there is still another tonal step available to us.

Step 11 – Strengthening the background

Now using a slightly thinner consistency, I paint over the background again. Notice how the paint colour appears warmer in tone because of the warmer underglow coming through.

Paints always look warmer in a thin layer and always go cooler as soon as you add white. Although this is a very simple point, it can be key in getting the most out of each pigment, rather than jumping to use a new colour.

Then, using a size 10 Ivory Filbert, I gently unify the tone to get rid of brush marks and fuse the edge between the hair and the background.

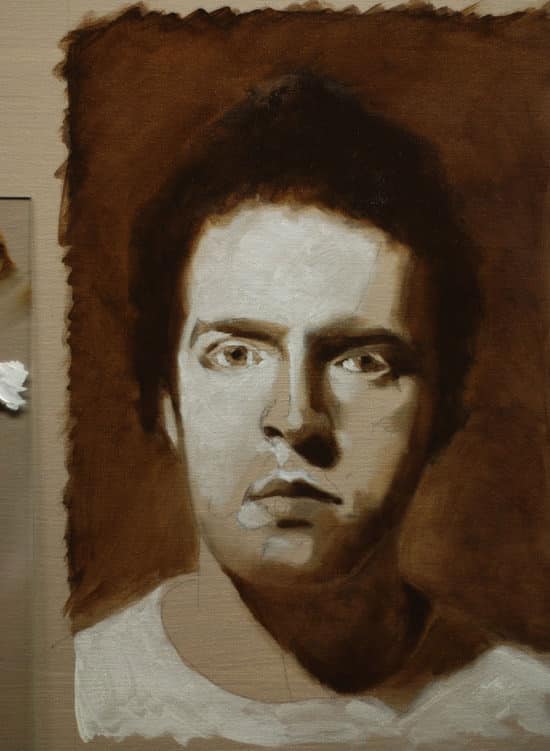

Step 12 – Introducing the Lights

“Most objects can be reduced broadly into three tone masses, the lights (including the high lights), the half tones, and the shadows. And the habit of reducing things into a simple equation of three tones as a foundation on which to build complex appearances should early be sought for”

Harold speed, The Practice and Science of Drawing

A note about underpainting white with acrylic paint

A note about underpainting white with acrylic paint

Pro tip: In this demonstration I under paint the lights with oil paint. However, if I’m working to a tight deadline and the ground has been prepared with an acrylic gesso there is another option that you can work an underpainting with acrylics.

Be careful not to paint too thickly or you will have a plastic resist to the oil paint, notice in part 1 how the coloured ground was applied thinly so the oil could still adhere to the canvas.

3 Different kinds of White

- Flake white – This is a lovely white that brushes out nicely and has a nice flexibility in the paint film. It is also a quick drier compared with Titanium white, so is useful for under paintings. This makes it a great white for mixing subtle tones when working with a full palette for oil portraits as you can shift the colour, yet still work in semi-opaque layers to develop the skin tones.

It has a semi-opaque finish and is the least white of the white. For finishing highlights or a really bright white, Titanium white is a better choice.

For this tutorial, it is not as important and you could use a Titanium white for the whole way through. This way you can get used to using thicker, more opaque colours that will help you to understand the basics of painting, rather than getting obsessed with the subtleties of glazing.

- Titanium white – I find this is the most opaque and bright white, it is a slower drier than Flake white and is very thick when it first comes out of the tube.

Pro tip: I often mix my Titanium white with OMS just to create a more flexible and free flowing consistency, I then keep a small blob of the pure white for adding the thickest, brightest highlights.

- Zinc white – Another semi-opaque white used for mixing and subtle-tinting of colours, I personally don’t use this much in my paintings.

Lead-based pigments:

The perception that “oil paints are hazardous” comes from the use of lead-based pigments.

Until the beginning of the 20th Century, lead whites were the only opaque white pigments available, Zinc white was available but had more transparency and a tendency to dry slowly, so was hard to paint thicker, solid colour.

In the mid-1920’s non-toxic Titanium White was introduced and gave artists a non-toxic alternative. So historically, painters have been exposed to much higher levels of toxic pigments than modern day painters.

However, some artists continue to use lead white because of its interesting working properties. Lucien Freud loved it so much he bought it in bulk, fearful Cremnitz white was going out of production.

A note about Lead Whites

- Flake White No. 1

- Cremnitz White

- Foundation White.

Lead white has been used traditionally by the Old Masters, and as such is often viewed in high regard. However due to the toxic nature of this paint, it is often only available in tins and recently has had issues with health and safety.

They are fast drying and offer a high degree of flexibility and as a result, they are often used for portrait work.

Specifically, Flake White No. 1 has a creamy consistency and handles really well.

Cremnitz White is ideal for achieving sculptural effects thanks to it unusual almost stringy consistency.

Foundation White is a traditional lead-based white, ground in Linseed Oil which thanks to its fast drying rate, is ideal for priming.

Please Note: Disposal of the lead waste from the painting process can be problematic. Throwing lead out with your regular rubbish is against the law.

Lead paint, the tubes it comes in, cloths and any solvent used for cleaning when working with lead, are considered hazardous waste and have to be disposed of at hazardous waste sites. (see comments below)

I’ve also seen that Gamblin produces a flake white alternative that is non-toxic. I haven’t personally used it but will look into doing a comparison post in the future.

Drying rates of oil paints

Oil paints that are slow driers should be avoided in the underpainting as it breaks our number 1 rule of ‘fat over lean’. When a faster-drying layer is painted over the top it will pull apart from the underpainting which contracts and gets smaller when it dries.

When working with the lights, you need an underpainting with a quick drying white. You could use Alkyd (quick drying oils), an underpainting white or, as I am using in this demonstration a Flake white.

When you are painting with a range of colours on your palette, the different drying rates of the oil paints are not as noticeable because you are constantly intermixing them. However, for the technique we are using so far, building up the painting in progressive layers, you need to be aware of the drying times of the pigments you are using.

How to speed up the drying rate

White (especially Titanium white) takes longer to dry than Raw umber.

If you are working on the underpainting and want the oil paints to dry quicker, you need to add a siccative.

A siccative is a name for a drying agent mixed in with the paint.

Traditionally in classical painting, cobalt driers were often used to accelerate the drying time of oil paint. Using a pipette, you can just add a couple of drops of cobalt drier to your paint.

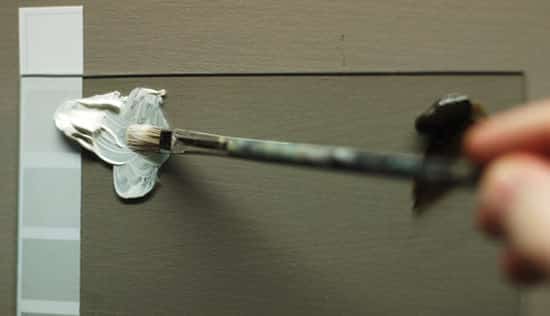

Mixing White for this layer

You’ve got 2 choices, if time isn’t an issue, mix your white as we did before in Part 1 with a little OMS, this way it will take a little bit longer to dry.

Alternatively, if time is an issue you can add a siccative.

For the initial white layer of the painting, I do add a siccative and the siccative I am using is Liquin. So what I do is mix a small amount of Liquin with the Flake white until it has a buttery consistency.

Please note: I don’t add any OMS or Linseed Oil.

Liquin speeds up the drying by about 50 percent.

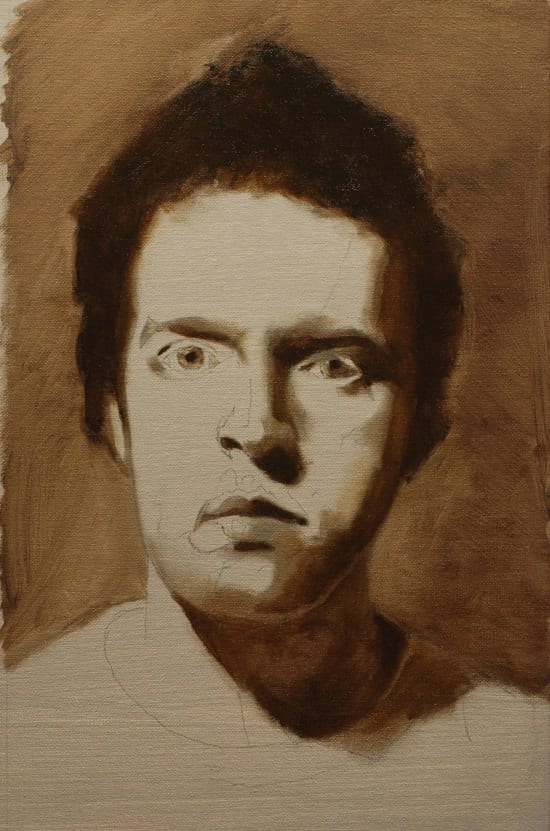

Notice how on the whites I block in the mix doesn’t completely cover the coloured ground.

With the white I am just painting the light side of the portrait, the lightest lights, leaving the coloured ground exposed on the right side of the portrait.

With the smaller round sable, I add lights around the eyes, I’m trying to establish a tonal range between the darkest darks and the lightest lights so I will be able to judge the next step easier when we mix our colour strings. Don’t worry if it’s not 100% accurate it is just a thin veil of paint to help our eyes judge tone.

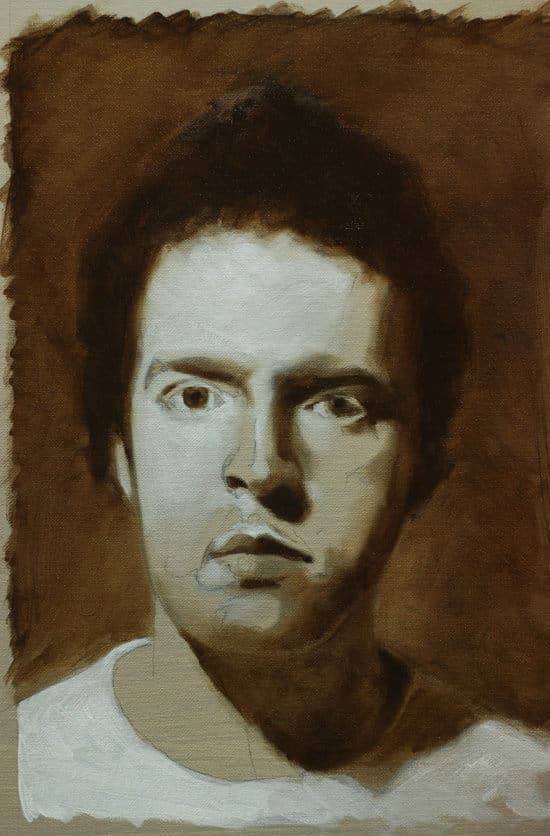

Step 13 – Softening the Lights

On this stage of the painting, I have softened the white edges on the face so again. I don’t have any sharp lines and notice once we are at this stage I then have gone in heavier to make the white on the T-shirt more opaque as I am more confident in matching the tonal value.

Great work! next week we can start to mix colour strings and model the form of our portrait.

Tune in next week for stage 3.

Happy painting!

You might also like:

1. How to Paint a Portrait in Oil – Part 1

2.How to Paint a Portrait in Oil – Part 3

3. Choosing a Basic Palette for Portraits