Caneletto, Venice, The Grand Canal, about 1740

Perspective techniques for absolute beginners

How to solve a problem like perspective?

Perspective is one of the most common issues beginners have with drawing and painting.

Get it wrong and it can easily ruin a great start, get it right and it can instantly improve your work.

If you’re like most painters you are probably trying to create a sense of depth in your work.

Leading the viewer’s eye deep into the scene giving the illusion of reality.

But sometimes it just doesn’t look right.

The distant object doesn’t look so distant, your figures look out of proportion, a building looks like it is sliding off the page. And your still life just looks….odd.

You are not alone….

Why is drawing perspective so hard?

This is one of the most common causes of frustration in learning to draw.

You can shade pretty well, you’ve got bold, expressive marks but your row of trees just don’t recede into the background as you would like.

Sometimes the biggest problem with perspective is the word ‘perspective’.

It is too off-putting and brings up memories of vanishing points and technical pencils, but perspective doesn’t have to be rulers and set squares just simple techniques to add depth to your paintings.

In practical terms when sketching, you don’t need to know ‘classical linear perspective’ you just need a few pointers.

Simple perspective principles

1. Overlap

This is the easiest way to add perspective and easily overlooked.

All you need to do is place one object in-front of the other.

Simple.

This helps your viewer to judge the relative size of an object.

In landscape painting, this can especially be hard to judge as a view could stretch back in the distance for miles but without the use of overlap, it can be hard to judge, just how far.

It doesn’t always have to be as obvious as a tree in front of a fence, overlap can happen everywhere, especially in nature.

Simply overlapping branches on a tree will give help to give the illusion of depth. Now this isn’t going to be Houdini standard illusion but in perspective, every little helps.

Pro tip: Length of shadow cast. If you have a jug in front of a box as in Chardin’s painting above, you can tell the distance by the length of the cast shadow it creates. Although not obvious, it helps our subliminal mind to make sense of the scene before us. Whereas in the first painting by Zurbaran, the perspective is very flat making it harder to judge relative sizes.

This simple positioning of objects can make a great deal of difference in creating the illusion of depth in your paintings.

Why?

It is very hard to judge the sizes and distances of objects if they are placed side by side on a surface.

You have to try and give the viewers clues to understand the relationship between objects.

Action step 1: Step-by-step perspective still life set-up

- Step 1 – pick two objects for a still life, we want action here so let us pick an apple and a cup.

- Step 2 – place them side by side on a table and lower your gaze flat on so you’re horizontal with the table and the table top disappears.

- Step 3 – analyze the view. which one looks further away?…It’s hard to tell.

- Step 4 – move the apple to the left to overlap the cup.

- Step 5 – check the negative spaces you have just created. This is key in creating a balanced composition

- Step 6 – turn off all lights in the room apart from one single lamp, a torch will also work. This will create a strong cast shadow. Move the apple closer to, or further away from the cup to start to see the effects of a cast shadow when creating the illusion of depth.

- Step 7 – draw it!

But I can’t draw! ….don’t worry, let’s look first at the science behind drawing.

Left Brain / Right Brain

As with most things drawing wise, in order to really ‘see’ a subject you have to learn the ability to trick your dominate left brain.

This is the logical, sensible side that likes to label things, order things, and always tries to ‘help’ your more creative right side when your are drawing.

By help, I really mean hinder. It means well but can quickly stop progression in drawing by being too clever for its own good.

Left brain thinking

If you know a chair has 4 legs but can only see 3 your logical brain tries to help you out and will urge you to draw in a fourth leg, even if you can’t see it from the angle you are looking at.

It is very powerful.

If you want to test your left brain/ right brain for drawing have a look at this experiment on the lateral thinking blog, it will mess with your mind!

How did you get on?

If you are naturally left brained, it will be harder for your brain to make the leap to a more spatially aware right brain, now I say harder, but not impossible.

If you draw what you see rather than what you ‘think you know‘ your drawings will be more realistic.

“An individual’s ability to draw is… the ability to shift to a different-from-ordinary way of processing visual information – to shift from verbal, analytic processing to spatial, global processing.”

Betty Edwards – author of drawing on the right side of the brain

Think abstract to create realism

You need to try and forget everything you think you ‘know’ about a subject in order to actually draw it as it appears.

If you are drawing a house in the distance, your left brain tells you a house is big, so even though you see it small, the tendency will still be to draw it slightly bigger.

Only slightly, you try to kid yourself.

It won’t make much of a difference.

However, all these slight alterations affect the overall sense of depth in a painting.

This can cause your drawings or paintings to look wrong or out of perspective very easily, there isn’t a huge margin for error.

Size and space

Tracing gets a bad rep, people think tracing is bad. Now I’m not talking about tracing over things you want to draw, far from it. I’m talking about using tracing as a method to help you learn to see.

To start with it is soooo helpful because you can create simple, in proportion views to work from. There is nothing like getting frustrated and stopping too soon.

So to understand the benefits of tracing we need to understand the picture plane.

What is the picture plane?

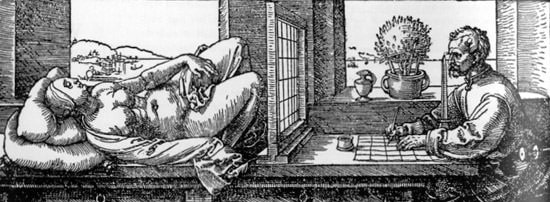

Albrecht Durer using an actual picture plane to aid his drawing, 1525

When you are learning how to draw, everything has to be envisaged through a frame, as all paintings and drawings exist within this.

If you imagine a piece of rectangular or square clear glass to be set up vertically between you and the things you are drawing or painting and imagine that you are actually seeing through the glass and simply tracing on it.

This is essentially all drawing is.

Drawing realistically is “copying” what you see on the picture plane.

So, the picture plane ‘exists’ in the mind’s eye, it is not a physical thing. It can be hard to get your head around it.

If your sitting at home, have a look through a window if you had a non-permanent marker you could draw around objects on the ‘picture plane’ on the window. This is an amazingly useful thing to do. It will highlight some key reasons why your drawings are going wrong.

Movement

If you move your head from a constant position the drawing on the window will not line up with the subject, this is key. Remember the story about the 3 legged chair? This is exactly what happens when you begin to paint. Your left brain tells you to “move round the corner,” so you can see the whole object rather than keeping in one position. You need to try and imagine your head is in a vice and can’t move from your chosen position!

If you ever watch an artist drawing you will see that their eyes are constantly moving but their head stays still. Beginners often move their head and keep their eyes on the paper rather than on the subject.

So let us get back to perspective..

Action step 2: Tracing scale

Step 1 – Find a picture that has a sense of depth, landscapes are perfect but you can watch my example if you want to.

Step 2 – Lay a piece of tracing paper or clear plastic over the image

Step 3 – Draw over, just with line, the things that are repeated, so in my example the buildings, this could be a row of trees or a row of telegraph poles. Ideally, an object that is similar in scale so not a house and a mouse!

This will be the biggest eye-opener. Objects get really small, really quickly and as the distance from the viewer increases the spaces between objects gets progressively smaller.

Scale

In the secret of good composition, I talked about the importance of variety in your work to help create a balanced composition and visual interest to your paintings.

When you are first beginning painting this simple trick of changing the size and space variations can help immensely.

So each gap between a row of fence posts will be:

- A different scale

- A different shape

- Get smaller into the distance

- Get shorter into the distance

- Appear closer together into the distance

However, even though we know this to be true, when it comes to actually drawing this effect of changes in size, we are often more cautious than we should be.

The actual changes in scale can be HUGE but it is hard for our logical side of our brain to realize this. We can measure them and ‘prove’ to ourselves they get smaller, but still, we can be hesitant when trying to draw something in perspective.

How to measure for scale

Have you ever seen an artist holding a pencil outstretched in front of them and squinting their eyes?

Wondered what they were doing?

It was a simple measurement.

Our brain can easily trick us when learning how to draw in perspective so a quick measurement with a pencil is a great tip to easily check your drawing.

You need measurements to notice:

- How far apart objects are

- Where the edges lie

- Relationships between the size of an object

- Centre line of an object

The simplest thing to use is your thumb and a pencil.

The 3 key points to remember are:

1. Make sure to lock your arm, this will keep the pencil at the same distance from the object. It is easy to forget this and have a slight bend in your arm, this will give a different measurement and may mean you unnecessarily change your drawing.

2. Try to keep your head still and view the subject from one position. It is like taking a really long exposure photo where your eye is the camera lens and can’t move its position.

3. Use a long pencil, with a flat top edge. This will mean you have room for maneuver when measuring a variety of objects.

How to measure subjects in a landscape with a pencil

- Lock your arm and hold it out in front of you so your arm is horizontal.

- You can use anything with a straight edge, pencil, ruler, knitting needle

- Close one eye

- Linen up the top of the subject you are trying to measure with the top of the pencil (or another straight edge)

- Move your thumb up the pencil to the bottom of the object you are measuring.

This gives you your first measurement. You now have to keep your thumb in this position so you can compare the length to another area of your drawing.

This can be on the vertical or horizontal, it is just to get a relative size.

Then if one section is the same length you can check this against your own drawing.

What matters is the proportion, not the actual measurement.

If you have a pencil and a window, experiment with doing some relative measurements even without drawing anything. It is best to use objects that recede into the distance that are the same, so a row of cars, the classic fence posts etc, etc.

Another easy tip to help you to see objects in isolation is just to roll up a sheet of A4 paper into a tube and use it as a viewfinder. This way you can judge its size in relation to the constraints of the tube rather than within a scene.

When viewing a whole scene our brain accepts everything in front of us, this is often why paintings have a flat or disjointed looking perspective.

Work within a frame

Have you ever started to draw in your sketchbook and run out of room? The model’s feet somewhere off screen? It is because you weren’t being specific about the edges of the image you were working within.

It is a useful trick to draw a frame border within your sketchpad so you have a clear edge to work towards. This will help you with composition, positioning, and scale.

Relative heights

It doesn’t matter if you can’t measure the exact ‘to the millimeter’ size of an object all that matters in a drawing is the objects relative size to each other so they look spatially correct.

In traditional Atelier painting, a knitting needle and plumb line are often used for measurement to create a traditional sight-size portrait.

The plumb line to enable you to judge your verticals as well as to check alignments between objects. For example, the alignment between the middle of an eye with the edge of a mouth.

Drawing and painting realistically are all about checking and rechecking your drawing. As you work longer on a subject you will notice more and more subtleties. Also, as your eye comes back fresh you will notice other areas that need changing.

Putting it all in perspective

Painting is always in a state of flux.

Beginners often get discouraged when they draw an object and say “Oh that’s wrong, I’m rubbish at drawing” whereas altering mistakes and fine-tuning details are all part of a drawing.

And let’s not forget, these techniques are to create realistic paintings and drawings.

If you prefer a more stylized or naive approach you could have a look at Cornish artist Alfred Wallis who had a unique approach to perspective.

Alfred Wallis, The Hold House Port Mear Square Island Port Mear Beach, about 1932

He painted the objects at a relative size depending on the size he deemed the most important to him. If a boat was the most important thing, that was painted the largest. One point perspective wasn’t needed as a more emotional response suited his needs. Don’t get hung up on getting everything perfect, just tweak a little at a time.

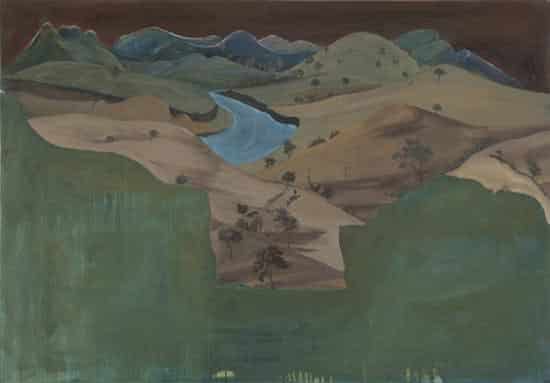

Another contemporary example, is Henriette Simson who has just won the £25,000 Threadneedle Prize

Henrietta Simpson, Bad government, After Lorenzetti

Her landscapes look at ideas around perspective, you can read a review on the winning piece at the Making a Mark blog

Resources:

1. Canaletto at the National Gallery, London

2. Alfred Wallis at the Tate Gallery, St Ives