An Artist in His Studio, John Singer Sargent, 1904

Last month saw the opening of a new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

The show highlights the work of one of my favourite portrait painters, John Singer Sargent (1856 – 1925)

I’ve been a fan of Singer Sargent’s paintings ever since visiting the Tate in London as 15 year old student, blown away by Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, the most compelling scene with its magical sense of glowing light.

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, John Singer Sargent, Oil on canvas, 1885

I’d always thought it was quite a small painting having only seen it in books, but in reality it’s nearly 2 meters tall by 1.5 meters wide, the sheer scale of it being life-size really draws you into the piece. The golden hour light is fading and the glow from the lanterns illuminates the girls faces so beautifully.

And that’s often the most fantastic thing about visiting an exhibition, the experience of sitting in front of the painting and seeing it through the artist’s eyes…

Although I’ve studied Sargent extensively in the past, this recent show Sargent, Portraits of Artists and Friends was a fantastic opportunity to see so many great paintings next to each other within the context of a timeline of Sargent’s life.

Many of the paintings in the exhibition were gifts to his friends, of his friends and fellow artists, in fact the two subjects in the painting above were the daughters of Sargent’s friend, the illustrator Frederick Barnard.

Sargent, Monet & Painting for Pleasure

Group with Parasols, John Singer Sargent, c.1904–5

Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of a Wood, John Singer Sargent, Oil on canvas, 1885?

The show revealed some connections I hadn’t noticed before and gave a fantastic peek into his thought process and experimentation’s as an artist.

I’d forgotten that Sargent was such a good friend of Monet’s. They’d met at an exhibition in Paris when Sargent was only 20 years old, he enjoyed watching Monet painting en plein air and his impressionistic, more gestural style influenced his own paintings – Sargent had been trained with a much tighter, classical painting technique.

He visited Monet at his studio and gardens at Giverny, France and painted him many times, often whilst Monet was at work sketching the landscape. Observing other artists for the pleasure of painting, totally away from the pressures of high profile commissioned clients, allowed Sargent to experiment with his style without the pressures of the formal sittings.

For me, this was the true essence of this exhibition, gaining access to Sargent’s work that was much more personal and intimate.

Throughout his life Sargent painted portraits of artists, actors and musicians, who were invariably his friends. Such pictures were rarely commissioned, and the artist was free to create more radical images than was possible in his formal portraiture.

Excerpt from the National Portrait Gallery Exhibition Catalogue

Portrait of Edouard and Marie-Louise Pailleron, John Singer Sargent (1881)

Alongside the more relaxed compositions, were detailed portraits that are fascinating to study for the pure technical brilliance of them.

One to look out for is this double portrait of the children of the playwright Edouard Pailleron. It’s a real masterclass in how to vary your brush marks, from the painterly impressionist Persian carpet to the finely painted hand and gold bracelet, to the highly detailed white fabric of the girls dress.

Sargent is epic at painting white!

He manages to represent the fall of the fabric, the sheen of the silk, the luminosity of the light hitting the subject without the feeling of it being overworked. For this painting, it’s worth getting your nose as close as possible to it without setting off the alarms!

Portrait of Claude Monet, John Singer Sargent, 1889

One of the other portraits that struck me was a side profile of Monet. It was interesting to see him without a hat! I think my romanticized view of Monet is always of him with a handful of brushes in hand, wide hat on head in his Waterlily garden!

Sargent’s paintings have that great mix of appearing more finished and realistic from a distance than they actually are when you study them up close. He practiced a painting method called ‘sight-size’, a technique where the key idea is that your eye needs to be able to see both the canvas and the subject in one glance, so they both appear the same size.

This makes it easier to flick your eyes between the subject and your painting for judging shape, proportions and colours. The artists viewing position is roughly 6 – 12 feet away from the set up, so you step forward to make a mark and then step back to observe your painting again resulting in a more painterly, naturalistic finish.

Sargent has a great knack for concentrating our attention on the key features, the nose and eye have a refined lightness of touch, in comparison to the bolder handling of the brushstrokes on the white of Monet’s shirt and back of the neck … that is until you step back about 6 feet from the painting and suddenly the whole portrait comes into focus.

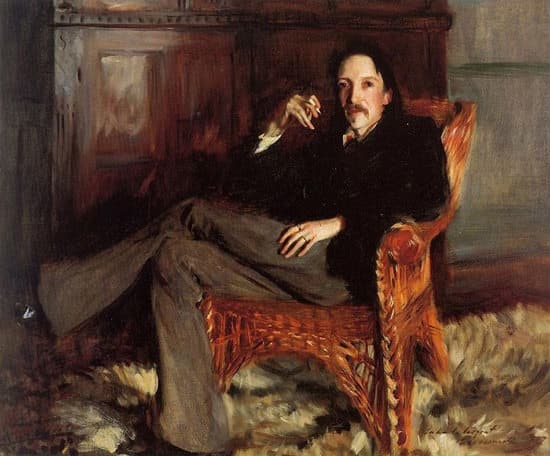

Robert Louis Stevenson, John Singer Sargent, 1887

The other thing I love about Sargent is his use of high contrast and black. Squint your eyes at this portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson, author of Treasure Island and you’ll see how his jacket and hair blend into the dark sideboard, placing the face in the highest contrast area of the painting.

He also draws our attention to the writer’s hands by painting them with more detail and refined modelling.

Also, his use of composition, especially in these more informal pieces is really contemporary and you can see a dark criss-cross pattern on the rug that helps to add lots of great diagonal lines to the composition.

These add to the already existing diagonal lines of his crossed legs and hand near his face, building on top of very gestural speedily painted brush marks on the back of the chair, resulting in a great sense of movement around the sitter.

You almost feel like his mind is whirring and this is one moment of calm before he uncrosses his legs and jumps out of the chair.

Sargent studied painting with Stevenson’s cousin at the Atelier of Emile Carolus-Duran in Paris, so knew the author for many years painting him at the height of his writing career.

Atelier of Emile Carolus-Duran

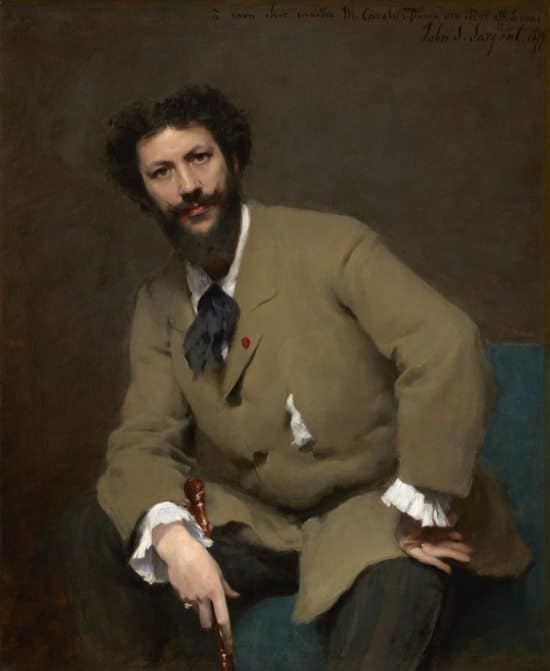

Portrait of Carolus-Duran, John Singer Sargent,(1879)

The other portrait I was keen to see in the flesh was his painting of the acclaimed french painter Carolus-Duran. Sargent studied under Duran at his Atelier between 1874-77, and he progressed so well they painted commissions together before Sargent set out on his own.

And just out of interest, Sargent was 23 years old when he painted this portrait.

I’d always loved the pose and gesture in the painting and the great handling of the sombre green hues. You will also notice another technique that comes up time and time again in portraiture, and that’s the arrangement of having skin tone next to black and then white.

This works really well because you can keep the hues between the skin tones very close in colour and tonal value but add variety and contrast to your portraits by the surrounding darks and lights.

It is extremely effective.

It’s all too easy to become addicted to glazes and overwork sections of your painting only to find you’ve lost some of that freshness and spontaneity.

I left the exhibition super inspired by the handling qualities of Sargent and the impact a few carefully placed direct brushstrokes can have.

There are so many great paintings in this show, if you get a chance to visit, it’s well worth it.

When you start your next portrait, load up your brush with colour, stand back from your easel and channel your inner Sargent!

The exhibition runs until May 25th at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

It is also touring to the MET in New York on June 30th – October 4th

P.S. I wanted to say hello to Cath, one of the students from the blog who happened to be visiting on the same day and spotted me in the gallery, I’d only been admiring her painting of a teacup a few weeks ago so it was great to put a face to a painting, so hello Cath!